Vine Management

Kiwiberry management is relatively intensive compared to other small fruit and berry crops in the northeast, including vining crops like grape. Because of its history first as an ornamental landscape vine then as a novel fruit for backyard growers and, more recently, permaculture enthusiasts, the species has several myths surrounding it, including that it requires little to no management to be productive (e.g. trellising, irrigation, pruning, fertilization, etc.) and is inherently unruly. Such ideas have persisted in part due to the fact that kiwiberry has received virtually no research attention as a commercial horticultural crop in the region. This narrative, however, is at odds with decades of experience of a handful of domestic growers, a growing body of international research, and our initial work here at the NHAES, all of which indicate that kiwiberries are highly amenable to intensive management and, in fact, require it for commercial production. When implemented properly, the T-bar system of kiwiberry production is demanding but manageable, with clear prescriptions for each stage of vine development. For a summary timeline of seasonal kiwiberry tasks, see Appendix VIII.

Vineyard layout

Assumed in the following discussion of vine establishment and management is a well-planned vineyard layout. As discussed in Vineyard Establishment, rows should be spaced a minimum of 10 feet apart (center-to-center), with larger alleys possible, as dictated by equipment access considerations. Within rows, the distance between adjacent vines varies greatly among production systems, with spacings of 8 feet up to 16 feet reported. An in-row vine spacing of 10 feet is the current recommendation for growers in the northeast. This relatively dense spacing is observed to be a reasonable compromise, resulting in a shorter time to full canopy coverage while still allowing for a sufficiently large root zone in fully matured vines. Vineyard layout should accommodate a minimum of one male for every eight females (see Pollination section for details).

Training young vines (years 1-4)

Year 1 – Root establishment

Young A. arguta vines are sensitive to extreme temperatures and drought; therefore, spring/summer transplanting should occur as soon as the danger of frost has passed and no later than late June. If emerging from a greenhouse environment, vines should be fully hardened off before transplanting lest they suffer from excessive transpiration or sun scorch. If protected from late season heat and drought stress, it is also possible to successfully transplant vines in the early fall, though the time between planting and the first expected hard frost should be at least a month to allow sufficient root establishment before vines transition to dormancy. Attempts at late season transplanting have resulted in higher levels of winterkill in the NHAES program, however, despite protective measures; thus spring/summer planting is recommended and is assumed throughout this section of the manual. Regardless of the timing, steady irrigation is critical during the period directly following planting.

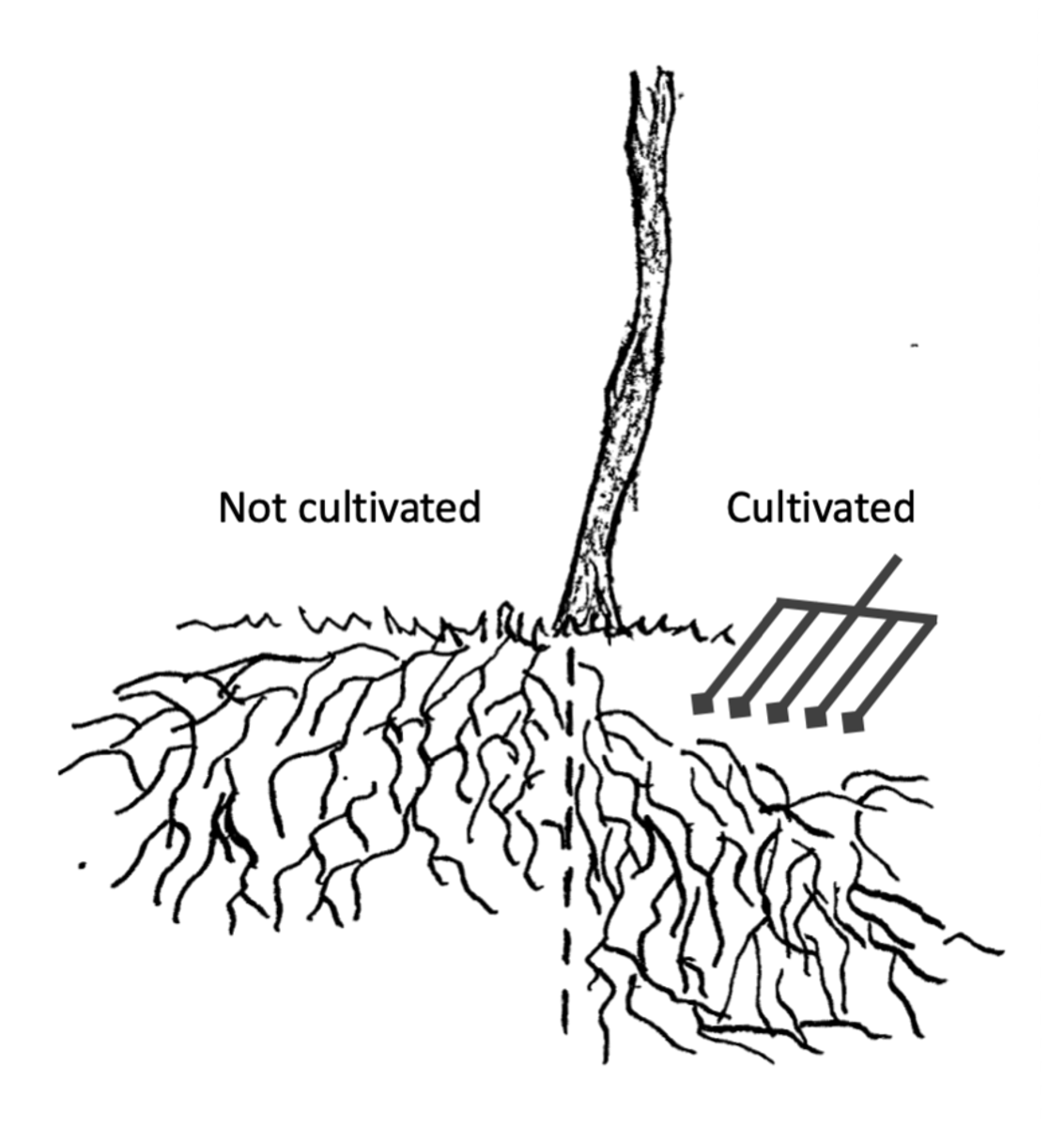

The primary objective of the first field season is to establish a robust root system that can support the vegetative growth required for the rapid development of desired vine architecture in subsequent years. Actinidia species have relatively shallow root systems, with ~90% of the roots of fuzzy kiwi vines found within 6 inches of the surface (Lemon & Considine 1993). To encourage root development, rootzone ‘training’ (i.e. light cultivation) is recommended throughout the season (Fig 24), in conjunction with mechanical weed control. Such training is also thought to encourage root development deeper into the soil profile; however, no research has been conducted to confirm or disprove this. In addition to root training via mechanical cultivation, investigations are currently underway at the NHAES to determine if subsoil root collars can encourage the formation of deeper root systems.

Year 2 – Trunk establishment

A vine well cared for in Year 1 will emerge from dormancy in Year 2 capable of producing and sustaining the vegetative growth necessary for trunk establishment. Strong architecture (trunk + cordons) is essential to long-term vine health and productivity; therefore, the objective of the second field season is the establishment of a straight and vigorous trunk. A strong, straight trunk is important for two reasons. First, straight trunks facilitate efficient vascular transport between the roots and the canopy. Second, straight trunks provide the structural integrity required to support heavy fruit loads and withstand weather events. As soon as new shoots are ~2 feet long, select a healthy, vigorous one to be the trunk and cut back all others back to the base, forcing the selected shoot to continue to grow. Subsequent removal of competing vegetative growth should occur approximately every 3-4 weeks throughout the growing season, with less attention needed during the mid-summer slump in growth (approximately mid-July to late August at the NHAES). As a rule of thumb, wait to prune competing growth until the longest unwanted shoot reaches a length of ~1.5 feet. Excessive pruning should be avoided because it can stimulate increased budbreak, resulting in unwanted shoot initiation and a cycle of increasing work.

If left to their own devices, kiwiberry shoots will attempt to climb by twining counterclockwise around whatever is nearby, including its own shoots. To obtain a straight trunk, it is necessary to actively train the selected shoot. To do this, we recommend securing the trunk to an 8 foot bamboo stake (Fig 25), securing it every 6-12 inches with a Tapener gun or similar tool for dispensing and securing durable trellising tape (see Appendix I ‘Grower Resources’). Training trunks or other parts of the vine (e.g. cordons and laterals) with rigid materials like wire ties is not recommended, as vines will quickly become restricted and begin to girdle as they continue to grow. Whenever competing growth is pruned, new succulent trunk growth should be untwined from the bamboo stake and secured straight before it begins to lignify.

Allow the trunk to continue to grow once it reaches the center trellis wire. At that point, it may be fastened to the center wire with a KiwiKlip or similar fastener (see Appendix I ‘Grower Resources’). If at least a month remains in the season before the first expected frost, you can cut the trunk approximately 6 inches above the wire to encourage cordon initiation (see next section). Remove all other emerging growth from the trunk, except for future cordons.

Year 3 – Cordon establishment

The establishment of permanent cordons is the focus of year three. Cordons are the primary horizontal growth of the vine, and the site from which all future fruiting laterals will emerge (Fig 26). Once a straight trunk has been established, it should be tipped ~6 inches above the center wire to break its apical dominance and stimulate shoot initiation along its length. Such shoots should be pruned as they appear, leaving only two opposing shoots within 6 inches of the trellis wire as cordons. As these cordons grow, they should be trained in opposite directions along the center wire. Similar to vertical trunk training against the bamboo stake, cordons should be trained as straight as possible with trellising tape against the center wire.

Once side shoots are selected and begin to be trained as cordons, the vine will assume a ‘T’ shape. Like the trunk, cordons may require a progressive sequence of shoots (i.e. multiple cycles of shoot initiation and growth) to achieve their final lengths (5 feet each, for vines spaced 10 feet apart in-row). If conditions are unfavorable and the vine has experienced temperature or water stress, trunk and/or cordon establishment can potentially span multiple seasons. Once cordons extend beyond their desired final lengths, they should be tipped to force lateral shoot initiation along their lengths. These lateral shoots (or laterals) are the fruit-bearing parts of the vine and are renewed annually (see next section).

Year 4 – Lateral establishment

After the first years of root system, trunk, and cordon establishment, the objective of subsequent years is fruit production through a systematic renewal of laterals. Kiwiberry vines bear flowers on wood that is at least one year old; therefore, the laterals selected and trained in one season become the fruiting wood of the following season. A lateral is trained by clipping it down perpendicularly to the trellis wires (Fig 27), such that it extends into the alleyway. Shoots from the cordon should be selected and laid down such that the resulting laterals are spaced 18-24 inches apart, with all other competing shoots removed (Fig 28).

Avoid selecting extremely vigorous, vertically-growing shoots for laterals. Such shoots, similar to waterspouts in fruit trees and dubbed “searcher shoots” by horticulturalists, are of generally greater diameter than other shoots and often break from the cordon in the process of bending them over. In later years, lateral spacing may increase as vines produce more fruit and fruiting spurs require more space.

When will a vine reach maturity?The establishment of good architectue (trunk + cordons + initial laterals) does not necessarily mean that a vine will begin flowering. The juvenile period of a transplanted vine may be as short as 2 years or as long as 6 or more, depending on variety, original propagation material, environmental conditions, and training. To accelerate the transition to reproductive maturity, vines should be intensively managed (i.e. competitive growth controlled) and protected from temperature, heat, and weed stress as much as possible. Well-trained vines not lacking for space, light, water, or nutrients will not only exhibit more vigorous growth but will also transition to reproductive maturity more quickly. In terms of production, a kiwiberry vine is only considered mature once it is able to generate sufficient laterals to replace those which fruited the current season. In general, vines will not reach commercial maturity (i.e. peak productivity) until a year or two after reaching reproductive maturity (i.e. 5-8 years after transplanting) (Strik & Hummer 2006), although some level of intermediate fruit production will be realized in the intervening years (see Enterprise Analysis). |

Pruning mature vines (years 4+)

Mature kiwiberry vines are vigorous, producing multiple rounds of large quantities of rapidly-growing shoots in a season. If not consistently maintained, plants can become tangled vegetative masses requiring a significant investment of time to return to productivity (Fig 29). For this reason, kiwiberry is not a hands-off crop to be left to grow on its own with only minimal maintenance. In addition to fertilization, irrigation, and weed control activities, prospective growers should plan for 1-2 heavy summer pruning events, interspersed with more minor pruning, as needed, in addition to a single heavy winter pruning event. Male and female vines require different pruning regimes; so the following discussion addresses them separately, by season.

In early 2020, Oregon State University produced an excellent set of video tutorials on pruning kiwiberry vines for commercial production (see Appendix I ‘Grower Resources’). The videos cover proper pruning of female and male vines, both during the growing season and while dormant. The content is behind a modest paywall, but we highly recommend it for folks unable to attend pruning workshops at the NHAES and indeed for anyone wishing to hone their understanding and skills.

Summer pruning

The purpose of summer pruning is twofold: 1) To direct desired vegetative growth and 2) To manage the canopy for light penetration (density of current and replacement laterals). As implied in the previous section on vine training, pruning directly affects growth. When a cut is made, a kiwiberry vine redistributes growth hormones, awakening dormant buds that become new points of growth, typically near the cut site. By understanding the response to pruning, growers can manipulate vine architecture, stimulating growth of a desired shoot to function as a trunk, cordon, or lateral. When pruning, it is important to consider not only current season goals but also future needs for lateral replacement and canopy renewal.

Female vines

Just prior to flower opening (anthesis), all non-terminating flowering shoots should be pruned back to the node beyond the last flower, thus preventing resource allocation to unusable growth and keeping the alleys clear. Following anthesis is a period of rampant vegetative growth, after which (approximately mid to late-July) vines should be pruned to increase light penetration through the canopy. Dense, heavily shaded canopies can result in premature fruit softening before desired sugar levels are achieved (Strik & Hummer 2006). Proper canopy thinning for light penetration improves fruit quality by increasing fruit total soluble solids and promoting blushing in certain varieties (Okamoto & Goto 2005). Beyond fruit quality considerations, vines with good light penetration are observed to be more productive than those which are heavily shaded (Strik 2005).

When pruning, it is important to consider the need for replacement fruiting laterals. Ideally, laterals should be spaced at 18-24 inch intervals along both sides of the cordon to form a uniform horizontal canopy. To ensure sufficient availability of replacement laterals, pruning should only be done to prevent excessive shading and remove unruly shoots during the vegetative growing season. As mentioned before, over-pruning can stimulate excessive shoot initiation in other areas, which not only wastes the vines energy but creates more pruning work downstream. The small, self-terminating spurs produced along the length of the cordons should not be removed, as they are often densely fruitful in later years. When pruning, cuts should be made at a 90-degree angle, just beyond a bud.

Male vines

The purpose of male vines in the vineyard is simply to produce pollen; therefore, the pruning strategy for male vines differs markedly from that for females. Put simply, males should be allowed to complete flowering, at which point (~ early-mid July) they should be pruned back heavily, with as much as 75% of the canopy being removed. In addition to removing all growth from the previous season (i.e. current flowering wood), new growth should be thinned out except for those shoots selected as replacement laterals. The desired distance between lateral shoots for males is 12 inches, significantly less than that for females. As the season progresses, males should be pruned back from the alleyways and from neighboring vines. Otherwise, any new shoots generated should be left alone, as they will bear flowers the following season.

General comments

For both males and females, unwanted growth elsewhere on the vine should be pruned. Whenever pruning the canopy, it is also important to remove all new shoots from the base of the vine (competing trunks) as well as any emerging along the trunk (competing cordons). Such clean-up greatly reduces the possibility of vines catching on vineyard equipment, encourages sub-canopy airflow, and avoids vine entanglement in irrigation hardware. Alleyways should be kept clear of reaching shoots which can pose a danger to equipment operators (Fig 30). In general, pre-emptive management of unwanted growth will lead to less work overall and provide a cleaner vineyard setting. All summer pruning should cease in September, or more generally at least a month before expected frost. Pruning beyond that time will only serve to encourage additional growth which will not have sufficient time to harden off and survive the winter.

Winter (dormant) pruning

Producers have some latitude in terms of when to conduct winter pruning, beginning as early as the first hard frost (D. Jackson, pers. communication) (~November) and as late as March, just prior to the initiation of sap flow. In the northeast, winter pruning typically occurs between January and March on fully dormant vines. If pruning late, it is advisable to verify vine dormancy by taking a few small, sample cuts and checking after 10-15 minutes for the presence of flowing sap (Fig 31). Pruning after spring sap flow may cause vines to irrevocably ‘bleed out’, especially if they experienced other stresses the previous season. It is possible that the recommendations presented above are conservative, as the actual sensitivity of healthy kiwiberry vines early spring pruning is not known. Particularly in well-established, mature vines, some growers report no issues pruning into the spring, despite sap flow (R. Guthrie, pers. communication). Such extended pruning practices are often done out necessity due to operation size and/or limited staff. One benefit of pruning kiwiberry vines late is the ability to better assess winter injury.

Female vines

Overall vine architecture is much easier to see in the dormant period, in the absence of obscuring vegetation. For this reason, the majority of the decisions regarding female vine architecture going into the next season should be made during the winter pruning period. To begin, all fruiting laterals from the previous season should be removed. Once removed, replacement shoots generated during the previous growing season should be selected and laid down, fixed to the outer trellis wires with clips. When thinning unwanted laterals, expect to remove up to 75% of the previous season’s growth (Strik 2005). While it may seem that you have removed an excessive amount of growth the first time you prune a vine this intensely, do not hold back. It only takes one season of dealing with a timidly pruned vine to change perceptions regarding pruning intensity.

Male vines

To ensure maximum flower set in the spring, male vines should only be pruned enough to remove rogue shoots from the alleyways. Any major tangles or dead wood may be removed, but the bulk of the previous season’s growth should be left until flowering has ended.

Fertilization

At present, there is relatively little scientific information regarding optimum soil nutrient content or nutrient requirements for kiwiberry vines at their various stages of development. While research along these lines is underway in both the Pacific Northwest and Europe, current best practices are largely based on the much better characterized production of fuzzy kiwis. As with any crop, it is strongly recommended that you perform a full soil analysis before implementing a soil amendment or fertilization plan because blind fertilization can be costly, both financially and environmentally. In the absence of specific soil tests for kiwiberry vineyards, growers should request a Commercial Orchard/Vineyard or Home Garden soil test, as common macro-and micronutrient recommendations for berry fruits provide a good starting point (P. Latocha, pers. communication). Nutrient testing is generally recommended once a season and should be done in the early spring (see Site Preparation section for details on soil sampling for analysis).

Taking residual soil fertility into consideration, kiwiberry fertilization consists mostly of split applications of nitrogen up through the middle of the growing season, with total dosages increasing as vines become established and transition to maturity:

Year 1 Young vines are extremely sensitive to fertilizer burn, so minimal fertilizer should be applied to new transplants. Specifically, apply 4 g (~0.15 oz.) elemental Nitrogen (N) per vine in three applications: May, June, and July. Evenly spread fertilizer in a 6-12 inch circle around the trunk.

Year 2 During trunk and early cordon establishment, apply 8 g N (~ 0.3 oz.) per vine per month in four applications: April, May, June, July. Increase the fertilizer application area to a 36 inch diameter circle.

Year 3 During initial lateral establishment, apply 16 g N (~ 0.6 oz.) per plant in three applications during: March, May, and July.

Years 4-5 For reproductively mature vines yet to reach peak productivity, apply 24 g N (~0.8 oz.) per plant per month in three applications: March, May, and July.

Years 6+ For fully productive vines, apply 36 g N (~ 1.3 oz.) per plant per month in three applications: March, May, and July. In Poland, four years of testing indicates that a soil N level of 50 ppm (parts per million) should be considered the minimum requirement for mature, commercial vines (P. Latocha, pers. communication); and growers should fertilize to this level, following spring soil analysis.

Assuming a plant density of 436 vines per acre (10 foot space between rows, 10 foot space between plants), the above fertilization schedule results in a maximum application of a little more than 10 lbs. N per acre in Year 1, up to nearly 100 lbs. N per acre for fully productive vines. Regardless of the stage of the vine, fertilization should not be done later than July as this can encourage excessive succulent growth that will not have a chance to harden off prior to winter. Excessive nitrogen applicatoin can also delay fruit development (Łata et al. 2018).

Regarding micronutrients, kiwiberry requires high amounts of potassium (K) and phosphorus (P), on the order of 80 – 130 lbs K and 55 lbs P per acre per year. While chlorine in very low concentration is considered to be beneficial for kiwiberry (F. Debersaques, pers. communication), fertilizers containing chloride should be avoided to prevent excess uptake and leaf burning (Strik 2005). Studies are currently underway in Europe to determine the effects and optimal levels of fertilization, including the nutrient sufficiency ranges in kiwiberry to enable informative foliar nutrient testing (Decorte & Debersaques 2017). Other preliminary studies indicate that calcium (Ca) plays an important role in maintaining fruit firmness during storage (R. Guthrie, pers. communication; Łata et al. 2018), but further work is required to fully characterize the effect of Ca and other nutrients on kiwiberry post-harvest performance.

Fertilizing based on cultivar?While the current practice is to treat all kiwiberries varieties alike, initial research out of Europe suggests there may be significant differences in nutrient uptake, allocation, and usage among cultivars (F. Debersaques, pers. communication). The potential to optimize fertilization based on variety is compelling, and further studies will be needed to determine such practices for regionally adapted cultivars. |

Cultivation

Once vines have been planted, the ground beneath a kiwiberry vineyard can be thought of as consisting of two functionally distinct areas: rows and alleys (Fig 32). Rows are the 2-4′ wide mulched and/or cultivated strips of land that run directly beneath the trellis wires and within which trellis support posts and vine trunks are centered. Alleys are the uncultivated but managed areas between rows planted to an appropriate cover (see Site Preparation section).

In the northeast, woodchips are a relatively available source of mulch for many growers. An application of mulch (5-7 inches deep) has been found to be an effective method for weed suppression over multiple seasons at the University of Minnesota Horticulture Research Center. When sourcing wood chips, select those with relatively low internal nitrogen content (e.g. those cut during winter) as these will not break down as fast as those with a high content (R. Guthrie, pers. communication).

Light cultivation of the rows is recommended to stimulate root growth in new transplants (so-called “root training”; see Fig 24), to encourage roots to grow deeper in the soil profile, and to manage weeds. Older vines not previously exposed to cultivation will suffer light initial root damage, given the shallow nature of their root systems, but will adapt over the course of a season with cultivation.

Rows should be wide enough to allow the chosen cultivation implement(s) to pass comfortably by vine trunks at a distance of no less than 6 inches (Fig 33). Based on the recommendations of experienced growers, the NHAES adopted a grape-hoe style cultivator for use in its research program (Fig 34; see Appendix I ‘Grower Resources’). Prior to trunk establishment, the cultivating fork is used for both root training and weed control. After trunk establishment, the hilling bar is used for ongoing weed control while developing and maintaining the raised beds. Side-mounted cultivators are ideal for kiwiberry production, as they allow for continuous cultivation between vines while moving down the alley. Frequency of cultivation depends on the rate of weed emergence. Factors such as volume of the weed seed bed, rainfall, and method of cultivation will impact timing. As canopies mature, weed competition will reduce dramatically as mature vines begin to shade out the understory.

According to one commercial grower, the long-term productivity of a kiwiberry vine depends on maintaining a proper overall mass balance between its roots and canopy (D. Jackson, pers. communication). According to this thinking, as a vine reaches 15+ years in age, its ever-expanding rootzone begins to overwhelm its regularly-pruned canopy, at which point it will transition to compensatory vegetative growth with reduced flowering. One possible strategy to prevent or postpone such a situation is to plant vines at a wider spacing (e.g. 16′ apart or more), though that will delay establishment of a full vineyard canopy. Alternatively, whatever the chosen vine spacing, an occasional pass (e.g. every 3 years) with a single shank chisel plow or spader may be done on older vines to deep prune their roots back to the confines of the row. It is important to note that these recommendations are speculative at the moment. The theory that long-term productivity may depend on maintaining a proper root-canopy balance is not uniformly shared among growers and is in need of research.

What about herbicides?The use of herbicides for weed control within kiwiberry vineyards is currently not recommended by the NHAES due to lack of information on their effects on vine health. We initiated a small investigation into the impact of herbicides in the summer of 2020 at the NHAES but do not expect results for several seasons. In Europe, Roundup has been observed to cause damage to young vines, even with no direct foliar contact (Debersaques et al. 2019). Whether absorbed through the roots or perhaps even the bark, the resulting damage is reported in some cases to take multiple years to become evident. Growers interested in trialing herbicides may wish to consider use of protective trunk guards and follow standard operating procedures to minimize unwanted drift |

Naturalized vines and invasive concerns

As the regional kiwiberry sector becomes established, it will become important to distinguish between ‘kiwiberry’ and ‘hardy kiwi’. The latter name is not only imprecise, applying generally to any cold-hardy kiwifruit species, it is also often negatively associated with locally-aggressive, naturalized vines hailing from A. arguta‘s earlier era as a minimally managed, ornamental vine in the region. In isolated locations in New England, some historic estate vines of A. arguta were abandoned. Such vines have since overgrown their original boundaries into surrounding forest (or in many cases the forest has grown up around them) and in some instances have generated progeny from seed (Fig 35). Though they respond readily to control measures, naturalized A. arguta vines can be a nuisance due to their ability to generate large amounts of vegetation which can create dense mats on the forest floor, reducing local plant diversity. They can also lead to increased ice and snow load in trees they have climbed, ultimately leading to their collapse. In stark contrast to these abandoned, ornamental vines, it is important to note that there have been no reported escapes of kiwiberry grown under managed cultivation for fruit production anywhere in the United States, despite thousands of tons of berries produced over many decades.

History teaches us that abandoned vines can, in some cases, become a nuisance. For this reason, it is important to properly decommission vineyards going out of production. Vines should be fully uprooted from the ground and the site rechecked in subsequent seasons for any re-shooting from residual roots. Vineyards left to outgrow their boundaries and expand unchecked into surrounding habitat can be ecologically and financially costly to those left to steward such areas. Additionally, such mismanagement could ultimately lead to dissolution of the entire regional kiwiberry industry. The most recent example of this risk was a proposal to add A. arguta to the list of prohibited plant species in Massachusetts in 2017. If approved, such a listing would have banned not only the propagation and cultivation of kiwiberry vines but also potentially the sale of kiwiberries themselves, even if they were produced outside the state. Fortunately, after a year of reviewing the available evidence, the MA Department of Agriculture rejected the proposal (see Appendix IV ‘MDAR decision letter’).

Moving forward, regional growers should be aware of this issue and manage their vineyards responsibly. Vines should only be grown in well-managed, trellised vineyards rather than allowed to grow unchecked on fences or arbors, as is sometimes suggested in backyard and permaculture grower guides (Affeld n.d.). Unwanted/damaged fruits should be disposed of in a manner which limits their access to wildlife, for example via incorporation into actively composting materials. Failure to follow such practices with excess fruit has resulted in the unwanted distribution of feral fuzzy kiwifruit vines in New Zealand due to the presence of the naturalized bird Zosterops lateralis (silvereye), which feeds on fuzzy kiwifruits (Sullivan et al. 2007).

Fig 24 In addition to controlling weeds, light surface cultivation (‘root training’) may help to redirect a kiwiberry vine’s normally shallow root system deeper into the soil profile.

Fig 25 A young vine during its first field season. A bamboo stake is used to train a straight and strong trunk.

Fig 26 Full cordon establishment is the objective of the second field season, although the process may extend into Years 3 or 4 under non-optimal conditions.

Fig 27 A new lateral trained to an outer trellis wire with a KiwiKlip (see Appendix I ‘Grower Resources’). Photo credit: I. Hale

Fig 28 A beautiful example of properly established laterals. Note the uniform spacing along the entire length of the cordon. Photo credit: Kiwi Korners/Kiwiberry Organics

Fig 29 Twisted and tangled vines are difficult and time-consuming to extricate from each other and can ultimately lead to reduced productivity if left unaddressed.

Fig 30 Unmanaged laterals allowed to reach into the alleyways can snag on equipment, posing a risk to both vines and operators.

Fig 31 Significant sap flow can occur if winter (dormant) pruning occurs too late in the season. While not necessarily an issue for well-established, mature vines, such “bleed out” can delay the development of young vines by as much as year or even kill them. Photo credit: I. Hale

Fig 32 There are two distinct areas in a kiwiberry vineyard: the rows or zones of production (vines and trellises) and the alleyways or spaces between the rows (vineyard floor).

Fig 33 The so-called “cultivation buffer zone” is the area indicated between the dashed lines above, 6 inches away from either side of the vine trunks. Weeds within this zone can be managed easily using a cultivator tool such as this hill-up bar.

Fig 34 At the NHAES vineyard, the cultivator attachment fabricated by GreenHoe of Geneva, NY, makes short work of weed removal.

Fig 35 A vine located on a former estate in Lenox, MA, which has outgrown the sunken garden it once occupied and climbed the forest which has grown up around it.